Lately I haven't been posting many updates on my dissertation, and I'd like to address the reasons. I have been focusing a lot of my attention on the Design Masterclass module, creating a presentation and game design document for the Ipswich Museum. The reason I've decided to prioritise this is because I have to give my presentation on the 7th of January, just under 3 weeks from now.

I feel that I can keep on top of my dissertation quite easily, but that I have to shift the timeline back slightly. Work will be very slow until this is over, but after the 7th of January, I will hopefully be able to give a lot of attention to the dissertation.

I also think that my presentation for the dissertation module on the 20th of January will be quite underwhelming, and that a lot of the contents are already available on this blog; I still,however, plan to make one or two more test animations and a storyboard to show off.

I update this blog with the progress of my 3rd year dissertation project: a 3D character modeled, rigged and animated in 3DS Max.

Wednesday, 18 December 2013

Tuesday, 3 December 2013

Jaunty Walk Cycle in Maya

Using what I've learnt in The Animator's Survival Guide, as well as my knowledge of graph editors and general animation in Maya, I've created a short walk cycle using the Max rig. I decided to make a cartoony walk cycle, so that I can give an example of 'expressive' movement, flinging his limbs all around him.

Although I'm happy with the result, I feel that some areas could use improvement, such as the arc of the arms.

Although I'm happy with the result, I feel that some areas could use improvement, such as the arc of the arms.

Wednesday, 27 November 2013

T.A.S.K. by R. Williams - Part 2: Character Movement

Pages 102 - 166 'Walks'

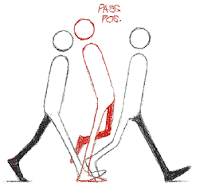

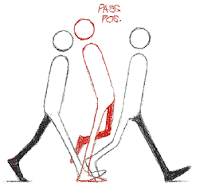

First we'll make the 2 contact positions. In a normal, conventional walk, the arms are always opposite to the legs to give balance and thrust.

Then we put in the passing position and because the leg is straight upon the passing position, it will lift the pelvis, body and head slightly higher.

Next comes the down position, where the bent leg takes the weight. In a normal walk, the widest arm swing is on the down position.

Next comes the down position, where the bent leg takes the weight. In a normal walk, the widest arm swing is on the down position.

It becomes more clear when spread out and exaggerated.

Set The Tempo

The first thing to do in a walk is set a beat. Generally, people walk on 12's - march time (half a second per step, two steps per second.)

Lazy animators don't like to do it on 12's, as it's hard to divide up; instead, do it on thirds.

Have the character walk on 16's or 8's, as they are easy to divide up.

We set a beat:

4 frames = A very fast run (6 steps per second)

6 frames = A run or very fast walk (4 steps per second)

8 frames = Slow run or 'cartoon' walk (3 steps a second)

12 frames = Brisk, business-like walk (2 steps a second)

16 frames = Strolling walk - more leaisurely (2/3 of a second per step)

20 frames = Elderly or tired person (almost a second per step)

24 frames = Slow step (one step per second)

32 frames = ...'Show me the way... To go home'...

The best way to time a walk (or anything else) is to act it out yourself and time it with a stepwatch.

The Passing Position or Breakdown

There's a simple way to build a walk. Start with just 3 drawings. Our two contact positions, and then put in a passing position.

This time it's raised higher than before, making it the 'up position', and the contacts will act as the low.

When we make the character go down on the passing position, it becomes a 'cartoony' walk, the passing position acting as the low and the contacts as the highs.

The crucial thing is the middle position and where we put it. Changing the middle position can give the walk a whole new feeling.

We don't have to stick to the same shape, there are things that can be done by changing mass.

How about a heavier man with a pot on him: instead of raising the whole body on the pass position, we can stretch it, giving flexibility.

Or conversely, squash it, giving more flexibility within the walk. Keep the pelvis level throughout.

A walk is the first thing to learn. Learn walks of all kinds, because walks are the toughest things to do correctly.

Walking is a process of falling over and catching yourself just in time. We're going through a series of controlled falls.

Usually we lift off the ground just the bare minimum, which is why it's easy for us to stub our toes or trip over.

All walks are different, no two people in the world walk the same. Everyone's walk is as individual and distinctive as their face, and one tiny detail will alter everything.

Women mostly walk with their legs close together, resulting in not much up and down action on the head and body.

Men walk with their legs apart so there's a lot of up and down action with each stride.

Getting The Weight

It's the up and down position of your masses that gives the feeling of weight.

It's the down position where the legs are bent and the body mass is down where we feel the weight.

This is what happens in a so-called 'normal' walk:

Then we put in the passing position and because the leg is straight upon the passing position, it will lift the pelvis, body and head slightly higher.

Next comes the down position, where the bent leg takes the weight. In a normal walk, the widest arm swing is on the down position.

Next comes the down position, where the bent leg takes the weight. In a normal walk, the widest arm swing is on the down position.

It becomes more clear when spread out and exaggerated.

Set The Tempo

The first thing to do in a walk is set a beat. Generally, people walk on 12's - march time (half a second per step, two steps per second.)

Lazy animators don't like to do it on 12's, as it's hard to divide up; instead, do it on thirds.

Have the character walk on 16's or 8's, as they are easy to divide up.

We set a beat:

4 frames = A very fast run (6 steps per second)

6 frames = A run or very fast walk (4 steps per second)

8 frames = Slow run or 'cartoon' walk (3 steps a second)

12 frames = Brisk, business-like walk (2 steps a second)

16 frames = Strolling walk - more leaisurely (2/3 of a second per step)

20 frames = Elderly or tired person (almost a second per step)

24 frames = Slow step (one step per second)

32 frames = ...'Show me the way... To go home'...

The best way to time a walk (or anything else) is to act it out yourself and time it with a stepwatch.

The Passing Position or Breakdown

There's a simple way to build a walk. Start with just 3 drawings. Our two contact positions, and then put in a passing position.

This time it's raised higher than before, making it the 'up position', and the contacts will act as the low.

When we make the character go down on the passing position, it becomes a 'cartoony' walk, the passing position acting as the low and the contacts as the highs.

The crucial thing is the middle position and where we put it. Changing the middle position can give the walk a whole new feeling.

We don't have to stick to the same shape, there are things that can be done by changing mass.

How about a heavier man with a pot on him: instead of raising the whole body on the pass position, we can stretch it, giving flexibility.

Or conversely, squash it, giving more flexibility within the walk. Keep the pelvis level throughout.

We can also keep on breaking things down into weird places, provided we allow enough screen time to accomodate the movement. Changing what happens on the inbetween positions can make the walk very different. You could make the character go down to take the weight, whilst still going higher on the push off.

Putting the down where the up would normally be and bending the leg, then where the down position was, put a straight inbetween but delay the leg for balance. This gives an interesting walk.

The Double Bounce

The double bounce walk shows energetic optimism - the North American 'can do' attitude.

The idea is 2 bounces per step, you go down (or up) twice instead of once each step.

The pass position is down instead of straight, so the character bobs up and down as he goes.

Weight Shift

The weight shifts from one foot to another in a normal stride. Each time we raise a foot it thrusts the weight of our body forward and to the other food.

The shoulders mostly oppose the hips and buttocks.

For fatter, more 'cartoony' characters, you can exaggerate the weight shifting.

The Belt Line

Tilt the belt line back and forth favouring the leg that is lowest.

Normally the belt line is down with the foot that is down, and up with the food that is up.

Also, the shoulder normally opposes the pelvis, but we can do what we like.

Pages 167 - 175 'Sneaks'

There are 3 definite catergories of sneaks:

The traditional sneak has an average of 24 frames for each step, and a fast version is 16 frames per step, with a slow version being 32 frames per step.

The three main things are:

- The body goes back and forth, the body goes back when the foot goes up. The arms are used for balance.

- When the foot reaches and contacts the ground, the body is still back and the head is held back, delayed just a bit.

- After the foot contacts the ground, the body follows - going forward as the foot takes the weight. Next, the body will go back as the other foot goes forward.

For a slow sneak, the arms don't oppose the legs, they just balance (generally little action happens in the arms and hands).

It's a good example of counteraction. As he moves along, the head goes forward and the hands go back.

Pages 176 - 216 - 'Runs and Jumps and Skips'

In a walk one foot is always on the ground, and only one foot leaves the ground at a time.

In a run, both feet are off the ground at some point for 1, 2 or 3 positions.

You only have to lift both feet off the ground for one pose to make it into a run.

The same thing can be done with more 'cartoon' proportions, with the feet off the ground for 2 positions, plus violent arm swings.

There is also the 'real' version of the same walk, with reduced arm action, hardly any up and down on the body, plus both feet are off the ground for 2 frames.

With walks, we can curve the body. Reverse it on the opposite step and keep it straight on the pass position.

We can't do as much as with walks, as we don't have as many positions because of the run is faster.

In a fast run #5 should not be exactly the same silhouette as it's counter, #1. Vary it, make it higher or lower. The positions should also overlap slightly to help carry the eye.

In reality the faster the figure runs, the more it leans forward.

We can take things much further with animation, leaning the body all the way forwards.

It's a good idea to vary the silhouettes on a fast run, so that the eye doesn't read it as just the same one leg and one arm going around.

T.A.S.K. by R. Williams - Part 1: History and Principles

I've recently read through The Animator's Survival Kit, a book which covers a lot of topics surrounding animation. Although the book mainly talks about 2D animation, a lot of the theories and principles apply to 3D as well. I will write a quick paragraph about the unimportant chapters, and go into more depth with subjects with will help me more with my dissertation.

Because each of the blog posts are quite long, I've split them into different posts to make it easier to read and find specific notes in future. I've given each of the posts a different heading to describe what is talked about in each.

Pages 1 - 40

Williams talks his career and experience with animation, and how he feels that it's important for animators to have good drawing ability; though he specially states that 3D animators don't necessarily need to have good drawing abilities, it does help to have a good understanding of anatomy and mass.

He suggests doing a lot of life drawing, which with time, can make even the most inexperienced of artists capable of drawing advanced creatures and scenery. Although I already have some basic drawing skills, I have taken his advice and have started doing some simple life drawings, and will continue to do so when I find the spare time.

Pages 41 - 83

Most of these chapters talk about how the 2D animation industry works, as well as the timeline of work and demands of employers. There is a lot of information about how to cut time using in-between frames and creating charts to explain what needs doing to assistants, who can fill in the unimportant drawings whilst the main animator works on the 'extreme' poses. Though very interesting, a lot of the information doesn't apply to 3D animation.

Pages 84 - 101 'More on Spacing'

This chapter starts to get more relevant to my work, so I'll make some notes below.

Classic Inbetween Mistakes

Richards writes about how 'inbetweeners' (frames which are not main poses) are often not done correctly. When making an inbetween frame, one should be able to understand and complete eccentric actions such as anticipation.

Most actions follow arcs, and generally an action is an arc. Arcs are usually wavelike or go in figure 8s. Sometimes arcs are angular or straight. Straight lines give power.

The arc of the action gives us the continuous flow, and the bones don't shrink and grow as they move - they maintain their length.

It all seems quite simple, but when we deal with sophisticated images and actions it can all go wrong.

Richards talks about a Hollywood assistant who was having trouble making a realistic horse animate correctly, and after looking closely at the arc of the eye, the problem became obvious.

Getting More Movement Within the Mass

This chapter is about finding ways to get movement within movement, getting more 'change', more bang for the buck.

To exaggerate a hit, such as a creature shooting through the air into a cliff, one could make sure he makes contact with the cliff before suddenly slamming into it. One could also stretch the creature before it touches the cliff, giving a stronger impact to the hit.

Because each of the blog posts are quite long, I've split them into different posts to make it easier to read and find specific notes in future. I've given each of the posts a different heading to describe what is talked about in each.

Pages 1 - 40

Williams talks his career and experience with animation, and how he feels that it's important for animators to have good drawing ability; though he specially states that 3D animators don't necessarily need to have good drawing abilities, it does help to have a good understanding of anatomy and mass.

He suggests doing a lot of life drawing, which with time, can make even the most inexperienced of artists capable of drawing advanced creatures and scenery. Although I already have some basic drawing skills, I have taken his advice and have started doing some simple life drawings, and will continue to do so when I find the spare time.

Pages 41 - 83

Most of these chapters talk about how the 2D animation industry works, as well as the timeline of work and demands of employers. There is a lot of information about how to cut time using in-between frames and creating charts to explain what needs doing to assistants, who can fill in the unimportant drawings whilst the main animator works on the 'extreme' poses. Though very interesting, a lot of the information doesn't apply to 3D animation.

Pages 84 - 101 'More on Spacing'

This chapter starts to get more relevant to my work, so I'll make some notes below.

Classic Inbetween Mistakes

Richards writes about how 'inbetweeners' (frames which are not main poses) are often not done correctly. When making an inbetween frame, one should be able to understand and complete eccentric actions such as anticipation.

Watch Your Arcs

The arc of the action gives us the continuous flow, and the bones don't shrink and grow as they move - they maintain their length.

It all seems quite simple, but when we deal with sophisticated images and actions it can all go wrong.

Richards talks about a Hollywood assistant who was having trouble making a realistic horse animate correctly, and after looking closely at the arc of the eye, the problem became obvious.

Everybody thinks they know the bouncing ball example, but swap the ball with a heavy billiard ball, and it won't bounce. Balls also wouldn't slow down as they fall, they speed up.

Getting More Movement Within the Mass

This chapter is about finding ways to get movement within movement, getting more 'change', more bang for the buck.

To exaggerate a hit, such as a creature shooting through the air into a cliff, one could make sure he makes contact with the cliff before suddenly slamming into it. One could also stretch the creature before it touches the cliff, giving a stronger impact to the hit.

Take The Long Short Cut

The long way turns out to be shorter, because something usually goes wrong with a short cut, and it turns out to take even longer trying to fix everything that went wrong. It's quicker to just do the work.

With animation, you have to be very specific. If a drawing is out of place, it's just wrong - clearly wrong- as opposed to 'Art' or 'Fine Art' where everything is amorphous and subjective.

It's obvious to us whether our animation works or not, whether things have weight, or just jerk about or float around wobbling amorphously.

There's nothing more satisfying than getting it right.

Tuesday, 19 November 2013

Proposal Marksheet Feedback

After receiving the feedback from the Dissertation Proposal, I feel that I should use this opportunity to answer some questions about it as well as discussing where I should go from here.

The first issue to tackle is that the elements that are being marked are not made clear. This is an issue I talked about very briefly at the start of the proposal, stating that I will only focus on the animations. That being said, I didn't mention the things that I wouldn't be animating, such as environments, models, textures, etc.. I will use a free, open-source rig from the internet (such as the ones exampled on this blog), and I do not plan to do any texturing or other work on the rig. As for the environment, I'm planning to stick to simple shapes (cubes, spheres, cylinders) for different surfaces and objects for the character to interact with; although I do not plan to be marked on texturing for the environment, I may put some simple patterns onto surfaces in order to easily distinguish them from the character.

The timeline is generic, but until I've done my storyboard, it's hard to know what needs animating. In hindsight, I feel that I should have allocated more time to planning the actual story, but I was told early on that the story isn't what's important, but the skills being demonstrated, so I ended up focusing on learning how to animate in Maya. As it stands right now, after exporting a very short animation from Maya, I can say is that most of the time will be dedicated to animating the character (which is extremely vague right now), and I can also safely assume that I will need at least 2 - 4 weeks to get the cameras set up correctly and render the final project.

I plan to make my storyboard very soon, which will give a clearer indication of how long each part of the animation will take. Until then, all I am certain of is that I will animate only the humanoid character, I will use simple directional lighting on the whole scene, and will export the animation as a 720p PNG image sequence into Sony Vegas, then convert it to a WMV or MP4 file. Without the storyboard it's also hard to know exactly what camera angles I will need to use, but I've animated cameras in 3DS Max in the past, and considering how easy I found it, I think the same ease will apply in Maya.

After recently trying to animate a face in Maya, it's actually a lot easier than I originally assumed. I therefore feel that including expressive facial animation is a good idea, but that I should do a little more research focused on it first.

Right now the next step forward is to draw out my storyboard, and then I can hopefully update my blog with a more acturate timeline.

The first issue to tackle is that the elements that are being marked are not made clear. This is an issue I talked about very briefly at the start of the proposal, stating that I will only focus on the animations. That being said, I didn't mention the things that I wouldn't be animating, such as environments, models, textures, etc.. I will use a free, open-source rig from the internet (such as the ones exampled on this blog), and I do not plan to do any texturing or other work on the rig. As for the environment, I'm planning to stick to simple shapes (cubes, spheres, cylinders) for different surfaces and objects for the character to interact with; although I do not plan to be marked on texturing for the environment, I may put some simple patterns onto surfaces in order to easily distinguish them from the character.

The timeline is generic, but until I've done my storyboard, it's hard to know what needs animating. In hindsight, I feel that I should have allocated more time to planning the actual story, but I was told early on that the story isn't what's important, but the skills being demonstrated, so I ended up focusing on learning how to animate in Maya. As it stands right now, after exporting a very short animation from Maya, I can say is that most of the time will be dedicated to animating the character (which is extremely vague right now), and I can also safely assume that I will need at least 2 - 4 weeks to get the cameras set up correctly and render the final project.

I plan to make my storyboard very soon, which will give a clearer indication of how long each part of the animation will take. Until then, all I am certain of is that I will animate only the humanoid character, I will use simple directional lighting on the whole scene, and will export the animation as a 720p PNG image sequence into Sony Vegas, then convert it to a WMV or MP4 file. Without the storyboard it's also hard to know exactly what camera angles I will need to use, but I've animated cameras in 3DS Max in the past, and considering how easy I found it, I think the same ease will apply in Maya.

After recently trying to animate a face in Maya, it's actually a lot easier than I originally assumed. I therefore feel that including expressive facial animation is a good idea, but that I should do a little more research focused on it first.

Right now the next step forward is to draw out my storyboard, and then I can hopefully update my blog with a more acturate timeline.

Monday, 11 November 2013

Another test animation

Using the Max rig in Autodesk Maya, I've made a silly animation to test out the leg, arm and face movements. It took a while to get started, but after a while I got the hang of it.

Next I want to work on slightly more realistic movements for the body and arm, and use the graph editor to smooth out every part of the animation.

Next I want to work on slightly more realistic movements for the body and arm, and use the graph editor to smooth out every part of the animation.

Wednesday, 30 October 2013

Mixamo

http://www.mixamo.com/editor/new/1896

Mixamo is a website I found which let's you view free and paid 3D animations. Although you can download them and edit them, my main use for the website is looking up specific animations (such as a running jump) and then using it as reference for my own character's running jump. On most of the animations you can change different aspects of them, such as the speed, arm/leg positions, framerates, and many more (see the link above for example).

After doing a few searching on it, I've found useful animations for walking, running, jumping, falling, and just about anything that I might get stuck on with my own project.

Mixamo is a website I found which let's you view free and paid 3D animations. Although you can download them and edit them, my main use for the website is looking up specific animations (such as a running jump) and then using it as reference for my own character's running jump. On most of the animations you can change different aspects of them, such as the speed, arm/leg positions, framerates, and many more (see the link above for example).

After doing a few searching on it, I've found useful animations for walking, running, jumping, falling, and just about anything that I might get stuck on with my own project.

Tuesday, 29 October 2013

Using free rigs

Over the last few days I've been trying out two different rigs and also been overcoming many problems with Autodesk Maya. I've started to realise how difficult it is to learn a whole new piece of software, and that I'm now very much against learning to rig as well as animate.

The main thing I've learnt is how important it is to set up the software correctly before starting. Although there are different ways to key in frames in Maya, I found that using stepped tangents works best for me. It allows you to block in key poses at the start, and then animate the transitions between them afterwards using the graph editor, instead of going through constantly to check the animation; this also makes it easier to work from a storyboard.

Here are a couple of the rigs I've tried out, both of which were recommended by 11 Second Club (http://www.11secondclub.com/resources), a website which hosts monthly character animation competitions.

Rig 1 - Moom

Moom was the first rig I tried, as I read some good reviews online and I like the art style of it. He's basically a cartoony character who you can squash and stretch into many different forms, making him versatile for comedic animations. It comes with a custom GUI which is used to select each point of the rig, rather than having controls in the main view.

The two downsides I found with Moom was that the custom GUI wasn't fully compatible with Maya 2014 (which is what I'm using), and that it was difficult to move his limbs in realistic ways because they stretched out and never retained their original proportions.

Rig 2 - Max

Max is an improvement over Moom for me, as he is easier to move around and his proportions always stay in check. The controls all work in the main view which allows for easier movement, and he also has good, simple facial animation tools so that if I did decide to put some focus on the face, this model would make that easy enough.

The only concern I could think of with Max is that he doesn't fit into my current story idea, but that doesn't seem too important as my story is not the focus for marking.

Rig 3 - Eleven

Eleven is a rig made by a group of contributors to 11SecondClub, and I feel that it is a perfect balance between the two rigs above. It's not extremely cartoony and un-realistic like the Moom rig, but it also has a good style and isn't as boring as the Max rig. The controls are very easy to use, and within minutes of editing it I was creating a variety of different emotions.

The main thing I've learnt is how important it is to set up the software correctly before starting. Although there are different ways to key in frames in Maya, I found that using stepped tangents works best for me. It allows you to block in key poses at the start, and then animate the transitions between them afterwards using the graph editor, instead of going through constantly to check the animation; this also makes it easier to work from a storyboard.

Here are a couple of the rigs I've tried out, both of which were recommended by 11 Second Club (http://www.11secondclub.com/resources), a website which hosts monthly character animation competitions.

Rig 1 - Moom

Moom was the first rig I tried, as I read some good reviews online and I like the art style of it. He's basically a cartoony character who you can squash and stretch into many different forms, making him versatile for comedic animations. It comes with a custom GUI which is used to select each point of the rig, rather than having controls in the main view.

|

| Setting up a few poses with Moom |

Rig 2 - Max

Max is an improvement over Moom for me, as he is easier to move around and his proportions always stay in check. The controls all work in the main view which allows for easier movement, and he also has good, simple facial animation tools so that if I did decide to put some focus on the face, this model would make that easy enough.

|

| Making Max jump a bit |

The only concern I could think of with Max is that he doesn't fit into my current story idea, but that doesn't seem too important as my story is not the focus for marking.

Rig 3 - Eleven

Eleven is a rig made by a group of contributors to 11SecondClub, and I feel that it is a perfect balance between the two rigs above. It's not extremely cartoony and un-realistic like the Moom rig, but it also has a good style and isn't as boring as the Max rig. The controls are very easy to use, and within minutes of editing it I was creating a variety of different emotions.

|

| Making a scared run |

Monday, 28 October 2013

Refining my job search

After getting feedback from my first proposal draft, I realised that I need to do more work on job searching. The problem was that my jobs weren't very relevant to what I want to achieve, and that I was focusing too much on what I can't do, rather than what I can do.

SAIC

http://jobs.saic.com/job/Huntsville-3D-Character-Animator-Job-AL-35801/15560600/?feedId=4&utm_source=Indeed

Blizzard Entertainment

https://blizzard.taleo.net/careersection/2/jobdetail.ftl?job=47480

Ubisoft

http://jobsearch.naukri.com/job-listings-Ubisoft-3D-Animator-UBISOFT-Entertainment-India-Pvt-Ltd--Pune-3-to-6-270513001307?xz=1_0_69&xo=&xp=3&xid=138296099781190400&qjt=&qp=3d+character+animator&id=&f=-270513001307

Some of the key requirements include:

SAIC

http://jobs.saic.com/job/Huntsville-3D-Character-Animator-Job-AL-35801/15560600/?feedId=4&utm_source=Indeed

Blizzard Entertainment

https://blizzard.taleo.net/careersection/2/jobdetail.ftl?job=47480

Ubisoft

http://jobsearch.naukri.com/job-listings-Ubisoft-3D-Animator-UBISOFT-Entertainment-India-Pvt-Ltd--Pune-3-to-6-270513001307?xz=1_0_69&xo=&xp=3&xid=138296099781190400&qjt=&qp=3d+character+animator&id=&f=-270513001307

Some of the key requirements include:

- Skills in animating human figures

This is the main skill I set out the learn, as I want to be able to create realistic human movement.

- Understanding of human anatomy, skeletal structure and musculature

Something I should research and learn more about, as it could be useful for understanding the limits of human movements.

- Self-motivation

Although I feel I'm already quite self-motivated, the dissertation should be a huge test of that.

- Knowledge of the principles of animation

This is something which I've already been resaerching, and will continue to do so (see 3D Art Essentials post)

- Able to work in team-based environment

Although not something I can easily learn from a solo dissertation, I feel that the negotiations between me and lecturers is a good example of a team-based environment, as I'm discussing and working based on others' feedback.

Wednesday, 16 October 2013

3D Art Essentials: Chapter 8 "Animation - It's alive!"

There is a practical task at the end of the chapter which I will do in another blog post later this week.

The Twelve Basic Principles of Animation

- 'The purpose of animation is to serve the story - to capture images of life, and in the process communicate to others, even if it just means giving them a thrill ride'.

- Animators at Walt Disney Studio wanted animation to feel real and allow audience to respond to character and story.

- They developed a set of animation guidelines which are still used to this day, though modified for computer animation.

Squash and stretch

- This is the most important principle.

- Bouncing ball is an example: as it hits ground it squashes, but its volume must stay the same, and it therefore stretches.

- Squashing and stretching give weight to objects.

- Isn't limited to balls and tummies, and collision with floors or objects is not required.

- These movements happen in facial expressions, and any other kind of motion.

- Bodies have weight and respond to gravity, they must retain their volume.

Anticipation

- Iron Man crouches and places hand on ground, and you know he's about to spring into action; this is an example of anticipation.

- It helps audience clue in that something will happen next.

- Anything which invites audience to watch what happens next is anticipation.

- If there's no anticipation, it can surprise the audience, if nothing happens, it's an anticlimax.

- Understanding this can help move story forward, set up comedic effects, or startle audience.

Staging

- Art of communcating idea clearly through imagery, be it personality, a clue, a mood, foreshadowing, etc.

- Is done with how character, objects and surroundings are presentated.

- Don't have anything unnecessary in scenes, or it will lose focus.

- Not real life, it's life through a filter; it is emotion, conflict, resolution.

- With computer animation, you have control over everything in scene and character, expressions, gestures; use this to your advantage.

- Staging can also be set in postproduction, with lighting and colour adjustments.

Straight-Ahead Action and Pose to Pose

- Styles of drawing your animation

- Straight-Ahead is animating frame by frame, it's good for dynamic action and spontaneity

- It can be bad because when hand-drawn, proportions and volume are lost, and you may end up at a dead end.

- Pose to pose let's animator carefully plan animation, draw key poses, then fill in movement between.

- Computer animation makes pose to pose natural, computer fills in movement between key poses.

- Motion capture and dynamic simulations are straight-ahead action.

Follow through and Overlapping Action

- When things like hair, clothing and loose flesh continue moving after character stops, it's called follow through.

- Could also be when characters move and things must catch up, or the expressive reaction of character to their action.

- Overlapping action is when things move at different rates, ie head turning whilst arm is moving

Slow In and Slow Out

- Action never stops instantly, or it's too robotic.

- Action starts slowly, speeds up, then ends slowly.

- Leave out slow in and slow out for surprise or comedy gags.

- Graph editor is good for creating this motion.

Arcs

- People, creatures and sometimes objects move in an arc.

- Try waving arm / hand, you can trace the arc it moves in.

Secondary Action

- Hair, clothes and background leaves are secondary actions to main character.

- They can be good for setting the stage.

- Can also show personality, such as how a character moving their arms while walking.

- If it distracts from main action, you need to eliminate or rethink it.

Timing

- Physical action is making sure the right actions occur at the right pace, in consistence to laws of physics.

- Cruise ship going to take longer to get under way than small yacht.

- Story timing is each shot, scene, and act; a part of both acting and storytelling.

Exaggeration

- Taking reality and making it more extreme.

- Realistic action and visuals fall flat when illustrated.

- Can be used for comedy, superheores, portraying mood, etc.

- Body, head shape, expressions, action, aspects of setting, storyline, anything can be exaggerated.

Solid Drawing

- Important to know where each muscle is placed before can be bulged out.

- Reference real life.

- Even if just interested in 3D art, take drawing classes and learn proportion, composition, perspective.

- Characters need to appeal to audience.

- If not sympathetic, villains can look cool.

- Has to do with features you give them, clothing, facial expressions, the way they act towards others.

- Symmetry is considered beutiful by people.

- Features that parallel the young (large head to body, large eyes, get more sympathy).

- For less sympathy, go opposite, with small beady eyes and narrow head.

- Must be believable, must be clear, audience must care about characters.

Keyframing

- Images that make up motion picture when sequenced are called frames.

- Typical framerates are 24 to 30 fps

- In 3D animation, computer renders each frame based on models, lighting, background etc and how you direct their movement.

- With keyframing, you define start, middle and ending positions and attributes of objects.

- Example of Susuan throwing a ball: start frame is when ball is in cocked hand, ending keyframe is when arm is stretched forward.

- Computer figures out frames that go between the key poses.

- New keyframes would need to be added to show the balls arc.

Animating with Graphs

- When you place keyframe, this will become a point on an animation graph.

- For the x axis of the graph you have the timeline, for y axis, the numeric value of object's attributes and position are shown.

- Computer interpolates between frames, and animation graph is where you see the values of the interpolation, drawn as lines of curves.

- There are three main types of interpolation.

- Stepped interpolation don't change until next keyframe, resulting in instant change from one to next.

- Linear interpolation connects keyframes by lines, giving smoother but still jerky movement.

- Curved interpolation connects points by curves, movement can be eased in and out to change speed.

- Manipulating curves on graphs is good for more exact animation, but should be used in conjunction with 3D view animation.

Motion Capture

- Motion capture lets a performer drive the animation of a character.

- Actor wears suit covered in lots of markers, sometimes on face for facial animation.

- Multiple cameras film them acting, then translate it into 3D space using markers.

- Rig must match up with actor well enough to give accurate data.

- Problems such as interacting limbs, body and face different from actors, and plain errors in capture.

- Animators must clean this up as well as exaggerate or enhance some poses, making it a collaboration between actors and animators.

Facial Animation

- There are six universal expressions: happiness, surprise, disgust, fear, sadness, and anger.

- Study expressions and get them right to avoid the uncanny valley, where expressions are close but not quite realistic, making the audience feel revulsion.

- Rig should involve deformation, skeleton rig with the jaw, good underlying topology.

- Use facial rig to create expressions called morph targets, which use sliders to move between two morphs.

- For talking, the sound of speech can be broken into phonemes.

- The shapes of jaw, tongue and mouth must make for phonemes can be called visemes.

- Problem with visemes is that they blend together during speech.

- Using sliders for morph targets and keying blended viseme in, can achieve more realistic speech.

- Important for mouth animation to sync to recorded speech.

- As well as speech track, you will have each sound plotted out to each frame.

Automation

- Lots of motion in animation can be automated.

- You can link any kinds of characteristics of objects to each other.

- The position of a switch can determine if light in the scene is on.

- As a cart moves forward, the wheels can turn at a rate which matches distance travelled to circumference of the wheel, making the wheel turn in time.

- Can also add animation without keyframing with dynamics and scripting.

Fence-Post Errors

- When filming at 24fps, a frame is captured over 1/24th of a second.

- In computer animation a rendered image only represents a point in time with 1/24th of a second between each frame.

- Can create fence-post errors, like when time is no longer moving forward so computer does not add motion blur where it needs to.

- Usually up to animator to correct such problems.

- Frames should be thought of as periods of time, not points in time.

Animation Workflow

- First few steps of a good workflow happen away from the computer.

- Should have a script by this point, may have a storyboard.

- During brainstorming, gather reference videos and pictures.

- Act out the motions yourself and get a feel for how it should go.

- A good animator is an actor who uses computer for their performance.

- Draw quick thumbnail sketches of ideas for poses, emphasis on quick as they are disposable.

- Brainstorming means quantity, not quality.

- Draw a pose, if it doesn't work, throw it out.

- These are key poses, and you need to consider timing of poses.

- Can arrange poses on exposure sheet (or 'dope sheet').

- Exposure sheet is used to write instructions for each frame, which gives a rough idea of timing.

- Once complete, get back to computer, take rigged model, and keyframe all poses.

- Work with heavy things first: legs, torso

- Work your way from main parts and big motions to tiny motions and facial expressions.

- Once all key poses are present, do a preview render whilst in stepped mode.

- Look at the timing and refine the pose positions.

- Character moves into poses at the same time, looking robotic.

- Could create more poses, the traditional method, gives more visual control and may save time with organization.

- Other method is modify poses using animation graph, to offset parts of the model.

- Don't render each section as you progress, refine whole shot then do another test render.

- Though most work is on refinement, if others can't see what's wrong, then it's fine.

- Some production houses have high quantity output, not quality; though something isn't good enough for you, it can be good enough for them.

- Most animating will be done with low poly versions of characters, as 3D modellers aren't finished; tweaks could be deleted and redone when final version is imported.

- Don't lose sight of the art, even if computers can do stuff for you, you may want to do it yourself; the computer has no heart or even a brain.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)