A walk is the first thing to learn. Learn walks of all kinds, because walks are the toughest things to do correctly.

Walking is a process of falling over and catching yourself just in time. We're going through a series of controlled falls.

Usually we lift off the ground just the bare minimum, which is why it's easy for us to stub our toes or trip over.

All walks are different, no two people in the world walk the same. Everyone's walk is as individual and distinctive as their face, and one tiny detail will alter everything.

Women mostly walk with their legs close together, resulting in not much up and down action on the head and body.

Men walk with their legs apart so there's a lot of up and down action with each stride.

Getting The Weight

It's the up and down position of your masses that gives the feeling of weight.

It's the down position where the legs are bent and the body mass is down where we feel the weight.

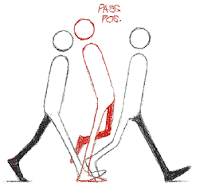

This is what happens in a so-called 'normal' walk:

Then we put in the passing position and because the leg is straight upon the passing position, it will lift the pelvis, body and head slightly higher.

Next comes the down position, where the bent leg takes the weight. In a normal walk, the widest arm swing is on the down position.

Next comes the down position, where the bent leg takes the weight. In a normal walk, the widest arm swing is on the down position.

It becomes more clear when spread out and exaggerated.

Set The Tempo

The first thing to do in a walk is set a beat. Generally, people walk on 12's - march time (half a second per step, two steps per second.)

Lazy animators don't like to do it on 12's, as it's hard to divide up; instead, do it on thirds.

Have the character walk on 16's or 8's, as they are easy to divide up.

We set a beat:

4 frames = A very fast run (6 steps per second)

6 frames = A run or very fast walk (4 steps per second)

8 frames = Slow run or 'cartoon' walk (3 steps a second)

12 frames = Brisk, business-like walk (2 steps a second)

16 frames = Strolling walk - more leaisurely (2/3 of a second per step)

20 frames = Elderly or tired person (almost a second per step)

24 frames = Slow step (one step per second)

32 frames = ...'Show me the way... To go home'...

The best way to time a walk (or anything else) is to act it out yourself and time it with a stepwatch.

The Passing Position or Breakdown

There's a simple way to build a walk. Start with just 3 drawings. Our two contact positions, and then put in a passing position.

This time it's raised higher than before, making it the 'up position', and the contacts will act as the low.

When we make the character go down on the passing position, it becomes a 'cartoony' walk, the passing position acting as the low and the contacts as the highs.

The crucial thing is the middle position and where we put it. Changing the middle position can give the walk a whole new feeling.

We don't have to stick to the same shape, there are things that can be done by changing mass.

How about a heavier man with a pot on him: instead of raising the whole body on the pass position, we can stretch it, giving flexibility.

Or conversely, squash it, giving more flexibility within the walk. Keep the pelvis level throughout.

We can also keep on breaking things down into weird places, provided we allow enough screen time to accomodate the movement. Changing what happens on the inbetween positions can make the walk very different. You could make the character go down to take the weight, whilst still going higher on the push off.

Putting the down where the up would normally be and bending the leg, then where the down position was, put a straight inbetween but delay the leg for balance. This gives an interesting walk.

The Double Bounce

The double bounce walk shows energetic optimism - the North American 'can do' attitude.

The idea is 2 bounces per step, you go down (or up) twice instead of once each step.

The pass position is down instead of straight, so the character bobs up and down as he goes.

Weight Shift

The weight shifts from one foot to another in a normal stride. Each time we raise a foot it thrusts the weight of our body forward and to the other food.

The shoulders mostly oppose the hips and buttocks.

For fatter, more 'cartoony' characters, you can exaggerate the weight shifting.

The Belt Line

Tilt the belt line back and forth favouring the leg that is lowest.

Normally the belt line is down with the foot that is down, and up with the food that is up.

Also, the shoulder normally opposes the pelvis, but we can do what we like.

Pages 167 - 175 'Sneaks'

There are 3 definite catergories of sneaks:

The traditional sneak has an average of 24 frames for each step, and a fast version is 16 frames per step, with a slow version being 32 frames per step.

The three main things are:

- The body goes back and forth, the body goes back when the foot goes up. The arms are used for balance.

- When the foot reaches and contacts the ground, the body is still back and the head is held back, delayed just a bit.

- After the foot contacts the ground, the body follows - going forward as the foot takes the weight. Next, the body will go back as the other foot goes forward.

For a slow sneak, the arms don't oppose the legs, they just balance (generally little action happens in the arms and hands).

It's a good example of counteraction. As he moves along, the head goes forward and the hands go back.

Pages 176 - 216 - 'Runs and Jumps and Skips'

In a walk one foot is always on the ground, and only one foot leaves the ground at a time.

In a run, both feet are off the ground at some point for 1, 2 or 3 positions.

You only have to lift both feet off the ground for one pose to make it into a run.

The same thing can be done with more 'cartoon' proportions, with the feet off the ground for 2 positions, plus violent arm swings.

There is also the 'real' version of the same walk, with reduced arm action, hardly any up and down on the body, plus both feet are off the ground for 2 frames.

With walks, we can curve the body. Reverse it on the opposite step and keep it straight on the pass position.

We can't do as much as with walks, as we don't have as many positions because of the run is faster.

In a fast run #5 should not be exactly the same silhouette as it's counter, #1. Vary it, make it higher or lower. The positions should also overlap slightly to help carry the eye.

In reality the faster the figure runs, the more it leans forward.

We can take things much further with animation, leaning the body all the way forwards.

It's a good idea to vary the silhouettes on a fast run, so that the eye doesn't read it as just the same one leg and one arm going around.